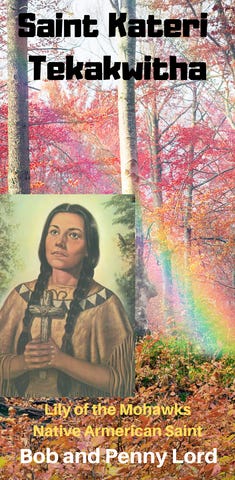

Saint Kateri Tekakwitha

Lily of the Mohawks

Mystic of the New World

Fruit of the Martyrs

The Video above on the Life of Saint Kateri has been made public as a perk to all members of Journeys of Faith Newsletter

The Lord takes us into the wilderness of a new, uncharted, untouched world, to share with us the beauty of His creation and the power of His works through the first beatified native person born in this country. In our book, Martyrs, They Died for Christ, we wrote about a new breed of Evangelists who came upon the horizon, whose images cast a broad shadow on a new world. These were brave, totally committed men of France, the Jesuit Blackrobes, who came to our continent in the early Seventeenth Century with only one goal - to bring Jesus to the pagans who inhabited the land.

The move by these French priests was spearheaded by an observation made by Samuel Champlain as he traveled the breadth of the St. Lawrence River, which then broadened out to Lake Ontario. He noticed as he sailed past all the Indian villages, there were so many children of God who knew nothing about Our Lord Jesus, our Savior. He wrote, in his journal, how sad it was that most of these people would live their entire lives never having heard the name of Jesus and would die without the grace of having known Him or being a part of His Church through Baptism.

When this word came back to the Church of France, an avalanche of fervor swept across the country. But it was the newly-formed army of Ignatius Loyola, the Company of Jesus, the Jesuits,1who took it as a call to spiritual arms. The French contingency of that order accepted the challenge put to them. They embraced St. Paul’s plea to the Christians of another time, the early days of the Church, as a call to arms. They used his words as their battle cry.

“For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

But how can they call on Him in whom they have not believed?

And how can they believe in Him whom they have not heard?

And how can they hear without someone to preach?

And how can people preach unless they are sent?”2

They came over to New France, as Canada was called at that time. They came with hearts burning to spread the word of God to the Indians and to die as Martyrs for Evangelization to the New World. By the thousands they came. They set up missions, worked in the wilderness, learned the language and customs of the Indians and gently, very gently taught them about Jesus. Their progress ranged from slow to full stop. But they persevered! They had many obstacles to overcome, many of which were caused by their own people. Before the Blackrobes ever got to Canada and upper New York State, they were preceded by trappers and fur traders who cared little or nothing for the people who lived on the lands, the natives of our country. They represented nothing but a way to satisfy their greed.

These were followed by the Military, whose only purpose was to obtain and maintain control and keep the Indians in their grip. Neither group would have won any popularity contests among the Indians. What they did manage to accomplish was to create an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust for any white men. The Blackrobes became victims because of the iniquities their countrymen and others3had inflicted upon the natives of America.

Add to that the Indians’ own culture, which was so completely different from the French settlers. Both the French and the Indians focused on the things which separated them, rather than try to find a common denominator- those qualities which could unite them. The Iroquois, who were the strongest of the Indian tribes, hated the Hurons, who traded with the French; therefore, the Iroquois hated the French. They were friendly with the Dutch and the British who were at odds and sometimes at war with the French. That could account for a great deal of the hostility between the Iroquois and the French.

But the real victims had to be the Blackrobes, the Jesuit Evangelists. They were blamed for everything. If the Iroquois attacked the Hurons, it was the fault of the Blackrobes. If the Hurons suffered drought, it was the fault of the Blackrobes. If the crops failed, it was because of the black magic of the Blackrobes. If illness were to take its toll on the Indian population, because of strains of bacteria, brought into the continent by the French, Dutch and British, it became strangely enough the fault of the Blackrobes. To this day, there are those in Canada who blame the Jesuits for the rampant disease to which the Indian population was subjected, and because of which they died in great numbers.

But what was the justification to blame the Jesuits? They were no more responsible for spreading the viruses than any other foreigner who emigrated to the country. However, they were the most vulnerable. They were the easiest to attack and the least able to defend themselves. There came a time in 1649, after the torturous execution of John de Brebuf, Gabriel Lalemant, and others in Huronia, when the wholesale slaughter of the Blackrobes became too much for the Superiors in Quebec to accept, and so they closed down the missions, burned to the ground Saint Marie of the Hurons, the settlement which they had built as a headquarters for the missionaries, and left to go back to Quebec. The mission venture to Huronia was a failure. The wilderness reclaimed the lands in which the Blackrobes had labored and died, their blood left as fertilizer for the growth of the new missions, the fruit of the Martyrs.

In Ossernenon, which is modern-day Auriesville, New York, the first of the North American Martyrs René Goupil was martyred in 1642, tomahawked for making the Sign of the Cross on a young Indian’s forehead. At that same place, St. Isaac Jogues and St. Jean Lalande, a lay Donné,4were martyred also. The Missionaries left and the cause seemed lost. But on that soil, in that place, the Lord was to plant the seeds of Evangelization into the blood-soaked earth, which would grow into what would be the first Native American Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, the Lily of the Mohawks, the Mystic of the Wilderness. And when she is canonized, finally brought into the Communion of Saints, she will be the first Native American, first fruit of the North American Martyrs.